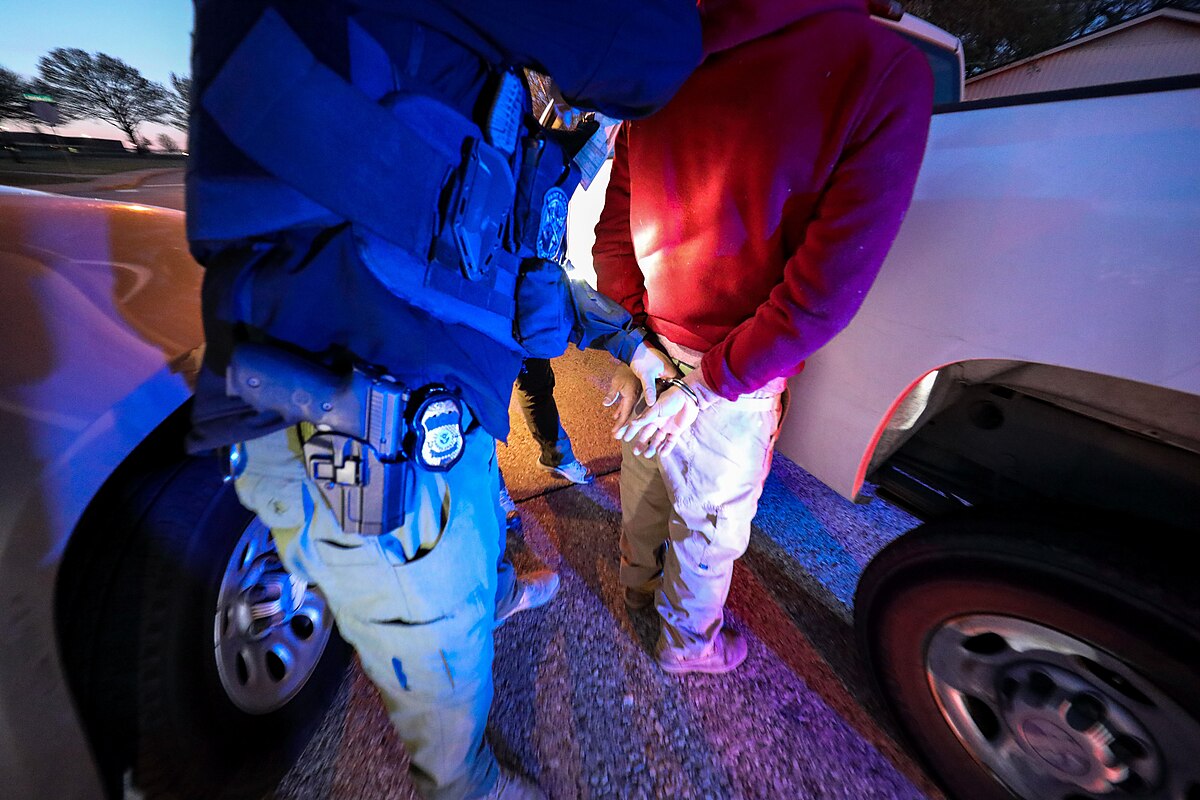

The more expensive concentrated-dose influenza vaccine is the choice of many seniors over 65 in the United States. However, this choice is not universal. Doses of the so-called “standard” vaccine are most often given to poor people from ethnic minorities such as Latinos and African Americans.

At Whitman-Walker Health, high doses of influenza vaccine are given to all HIV-positive and elderly patients. Although the vaccine is about three times more expensive than the standard flu vaccine, it appears to have a greater protective effect among people with weakened immune systems — a key focus of the nonprofit group's Washington clinics,

according to "The Washington Post”.

Meanwhile, at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque, there is a drive-thru clinic that delivers 10,000 flu shots a year to a community made up mostly of black and Hispanic residents. It is open to all interested and everyone receives the standard vaccine.

“These different approaches to preventing influenza, a serious threat to the young and old even with the coronavirus that causes Covid-19 on the scene, reflect how federal health officials haven’t taken a clear position on whether the high-dose flu vaccine — on the market since 2010 — is the best choice for older people. Another factor is cost. While Medicare reimburses both vaccines, the high-dose shot is three times more expensive and carrying both vaccines for different populations requires additional staffing and logistics”, as reported by the publication.

Clinics that provide doses of the standard vaccine seek to vaccinate as many people as possible, until the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s "Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices" decides whether to broadly recommend these improved vaccines.

The Washington Post report also points out that “In a given year, most influenza vaccines are not very effective. Drug companies vying for market share aren’t generally motivated to compare them, since they might lose out. And federal officials generally don’t fund such studies, so they are left to rely on research offered by the companies.

Meanwhile, older minority patients, especially Black seniors, are getting the short end of the stick, say some advocates for eliminating racial disparities in health care. Blacks are about 20 percent less likely than Whites to get flu shots, although they are at higher risk of severe flu. Even those who get the vaccine are about 30 percent less likely to get the high-dose version”.

A CDC working group has been investigating the matter since before the pandemic. On February 23, commission members reviewed evidence that the high-dose flu vaccine and two other improved versions of vaccines (one containing an immune-enhancing substance, the other a recombinant protein) performed better than the “standard” or low-dose vaccine.

The commission could vote at its next meeting, likely in June, on the matter. It is estimated that changing the vaccines given to all the elderly could reduce flu-related hospitalizations in the thousands per year, according to a study by the laboratory “Sanofi”.

In a more recent, yet-unpublished survey that included data up to 2018, Salaheddin Mahmud, director of the University of Manitoba’s “Center for Vaccine and Drug Evaluation” and first author of the report, which was funded by Sanofi, found that Southerners were less likely to get the high-dose vaccine than other Americans, and high-dose vaccine appeared to be less available in communities where more than 20 percent of the population were minorities.

It is noteworthy that, for decades, people who receive the standard vaccine quite disproportionately are Latinos and African Americans, according to a study by

The Lancet for the 2015-2016 flu season commons.wikimedia.org

commons.wikimedia.org