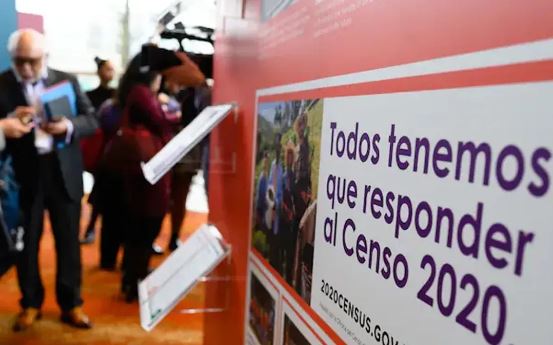

Black, Latino and Native American communities were underestimated in numbers in the 2020 Census, raising skepticism about the accuracy of the data. According to the analysis published by

The Washington Post, the census still faces a fundamental problem: “The census’ measurements of race and ethnicity overlook Afro-Latinos”.

However, even as the census improves its methodology, selection and counting still render some identities invisible. While polls treat black Latinos as Latinos, US society and institutions treat them as black based on their appearance. “Afro-Latinos’ looks can determine whether they are seen as professionals or as dangerous, as citizens to be protected or threats to be detained. As such, Black Latinos experience higher rates of discrimination than non-Black Latinos”, according to the analysis.

Before 1960, a federal “enumerator” (census official) identified a respondent’s race, not the respondent themselves. Neither Black nor White Latinos had the option of identifying as Latino or Hispanic. Under a 1930 rule, an enumerator would record someone with even just “one drop” of Black blood as “Negro” and others as White.

“Then the 1930 Census added the ‘Mexican’ race category. Latino interest groups opposed this addition, fearing negative social and political consequences. In the 1940 Census, Mexicans and other non-Black Latinos were categorized as ‘White’ again”.

“In 1980, the census included a ‘Hispanic origin’ category, allowing Black Latinos to count themselves among other Hispanics. However, until 2000, individuals were limited to one racial identification, inaccurately recording the many Afro-Latinos who identify as mulatto or mixed race”, according to The Post.

Today, the modern census uses five racial and ethnic categories: 1) White, 2) Black or African American, 3) American Indian or Alaska Native, 4) Asian and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 5) Hispanic origin.

The analysis also points to an essential problem: “The ‘Hispanic origin’ category reflects a 1970s reversal by Latino organizations, which began pressing for an umbrella ‘Hispanic/Latino’ ethnic category to secure federal funding and protections. This created a Latino identity coded as White or mestizo and non-Black. This reflects what I call ‘minority racial essentialization’, a process in which a racial category becomes equated with the image of the group majority with leadership power. As non-Black Latino leaders mobilized to add the ‘Hispanic’ category, Black Latinos were neglected by federal funding and political action”.

Thus, conflating “Latino” with Spanish-speaking is an aspect of “racial essentialization” because it leaves out Latin American countries with the largest black populations, such as Brazil and Haiti, and includes European Spaniards, who enjoy the privilege of being European and white.

Under the 2020 Census race questionnaire, “Haitian” is listed under “Black,” and no other Latin American country is listed as an example. In contrast, examples of “White” origins exclude any Latin American countries, even those well known to have greater than average White populations.

“While the U.S. Office of Management and Budget states that the goal of the Hispanic origin question guidelines was to enforce civil rights and equal access, it fails to provide equality for the Black Latinos who are most vulnerable to discrimination. They are either concealed within a broader Latino identity or excluded if they are Haitian or Brazilian. This has structural downstream effects, making Black Latinos invisible to U.S. institutions, and hence leading to their willful or accidental neglect”, completes the analysis.

Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post

Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post