- 14 3402-5578

- Rua Hygino Muzy Filho, 737, MARÍLIA - SP

- contato@latinoobservatory.org

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

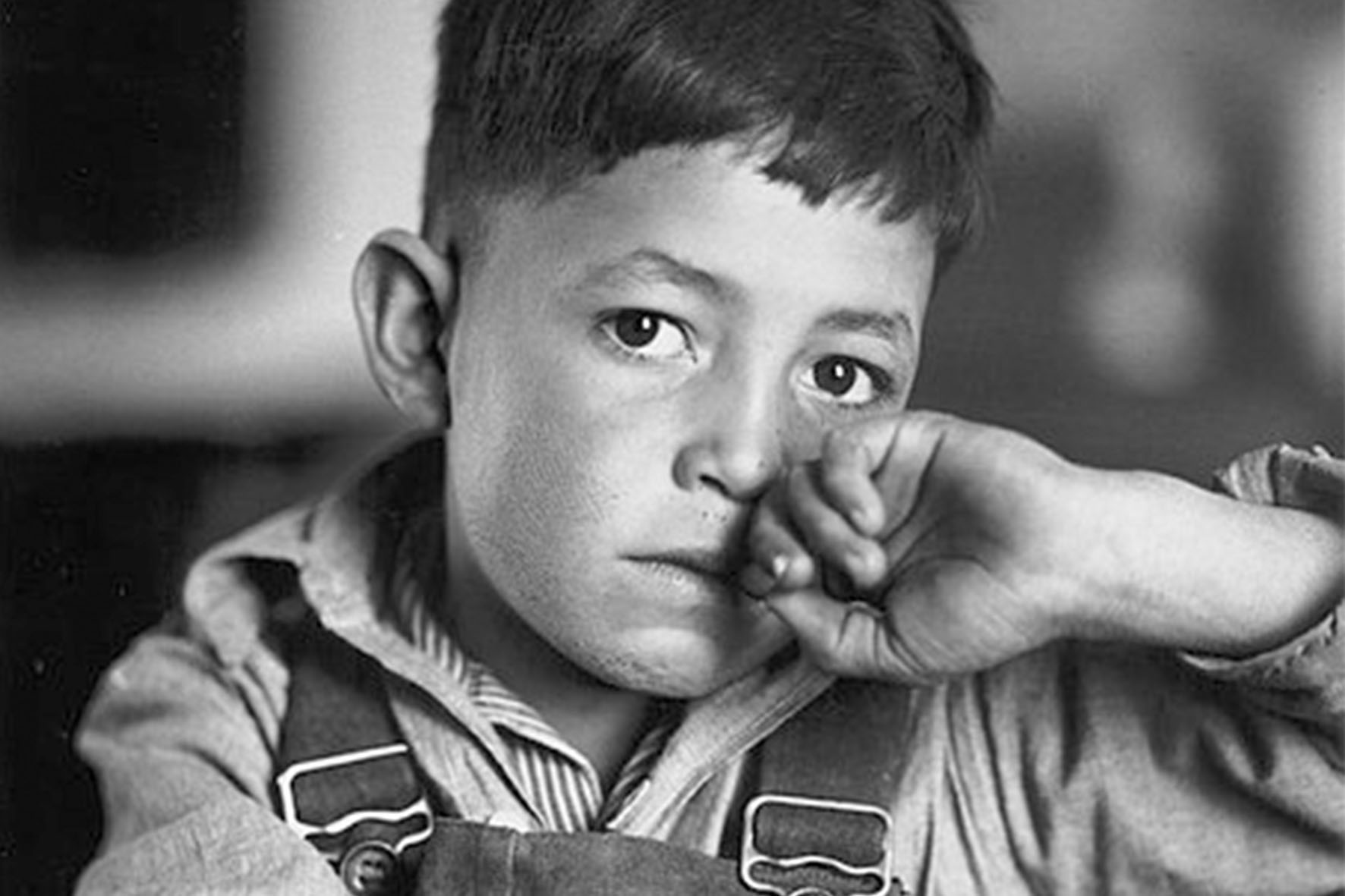

A special publication in The Washington Post called “Growing Up Latino”, in honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, sought the voices and stories of five children to describe what it's like to grow up being Latino in the United States in 2022. In this special, Latin children narrate how they are discovering their place in the country as they walk into adulthood.

According to the article, “More than a quarter of children growing up today in the United States identify as Latino, a percentage expected to grow in the coming decades. They live across the United States, from smaller suburbs like Commerce City, Colo., to metropolises like New York City. Some hail from families that have spent generations laying roots in this country, while for others, the U.S. journey has just begun. Around 95 percent of Latino children were born in the United States — their lives inherently American and Latino”.

Growing up Latino includes elements of life that all Latinos share and others that are distinct. Being a Latino child in the United States is also hearing their name mispronounced by strangers, being considered foreign even if the United States is the only country they know or is the one in which they live now.

The Post brought together narratives from five Latin children: Manuela, Isabella, Joshua, Manuel and Amanda. We selected some excerpts from these stories told from the point of view of each of them:

Manuela De Armas wanted nothing more than to change her name. She was one of four Venezuelan students at her elementary school in a South Florida suburb. And she didn’t like feeling different.

“I don’t have enough memories of Venezuela for me to truly miss it”, she said.

“It’s that lack of memories that can sometimes feel isolating. Having lived most of her life in the United States, she is sometimes perceived as too American — or gringa — by her Venezuelan loved ones. For her American friends, she seems too Latina”.

Isabella does not know another Cuban girl her age in Omaha. She is growing up 1,500 miles away from the land her grandparents once called home — Cuba. For her dad, raising her to feel like a cubanita is a top priority.

“The 7-year-old goes to a bilingual school, though most of her classmates who are Latino are Mexican American, not Cuban. He feeds her a mix of traditional Cuban and American food, from chicken strips and hamburgers to platanitos and picadillo. On the afternoons when Isabella turns on the TV, many of the shows are dubbed in Spanish — a function her dad discovered on the remote and has kept permanent to help her learn the language. Although part of the Cuban influence in the house is natural, her parents also acted intentionally to keep it alive”.

Born and raised in New York, Joshua Reyes grew up surrounded by a large Dominican population in a neighborhood where speaking Spanish, dancing bachata and eating mangú were the norm.

“Then five years ago, Joshua, 14, and his mom, sister and uncle moved to Allentown, Pa. — parting ways with New York’s fast-paced life and with the cultural bubble that made it easy to feel at home”.

“It’s hard to not really have as many people anymore that you relate to”, he said. “But now I’m kind of getting into the gist of it. I started meeting other Latinos but also making friends with more White people. I’m really seeing that barrier breaking down”.

Manuel Guardiola, 12, lives with his mother, Maria, who is raising four children in the Denver suburb of Commerce City. From the day he was born, Maria recognized the importance of him growing up feeling American.

“He is aware of her status — that his mom could get stopped by law enforcement and deported back to Mexico. But he tries not to worry”.

“I think it’s unfair,” Manuel said. “People should be able to get papers and have a better life here”.

“Maria said she tries to shield Manuel from some of the stresses and struggles in their family. Manuel’s father, 68, recently retired and is on dialysis. They’re relying on his pension alone to make ends meet”.

Living a few steps from the U.S.-Mexico border means Amanda Ortiz has never felt displaced being Latino in the United States. That's all she sees around her: Brownsville, her hometown, is 94% Latino.

“I’m with my people. And if I wasn’t with my people, I would feel out of place, and that’s even worse,” she said.

“Many in Amanda’s extended family, and most people around her, have lived on the U.S. side of the border for generations. Despite that, she said, Latinos in Brownsville often feel forgotten. Jobs are limited in the Rio Grande Valley. The area has one of the highest poverty rates and highest uninsured rates in the state”.

“Every year, Amanda expresses her heritage in Charro Days, a four-day festival for the residents of Brownsville and their counterparts on the Mexican side of the border, Matamoros”.

“I am very proud because I know some people do

not have the freedom to come over to America,” she said, “and I’m thankful that

my ancestors came to America so that I could have a better life”.