- 14 3402-5578

- Rua Hygino Muzy Filho, 737, MARÍLIA - SP

- contato@latinoobservatory.org

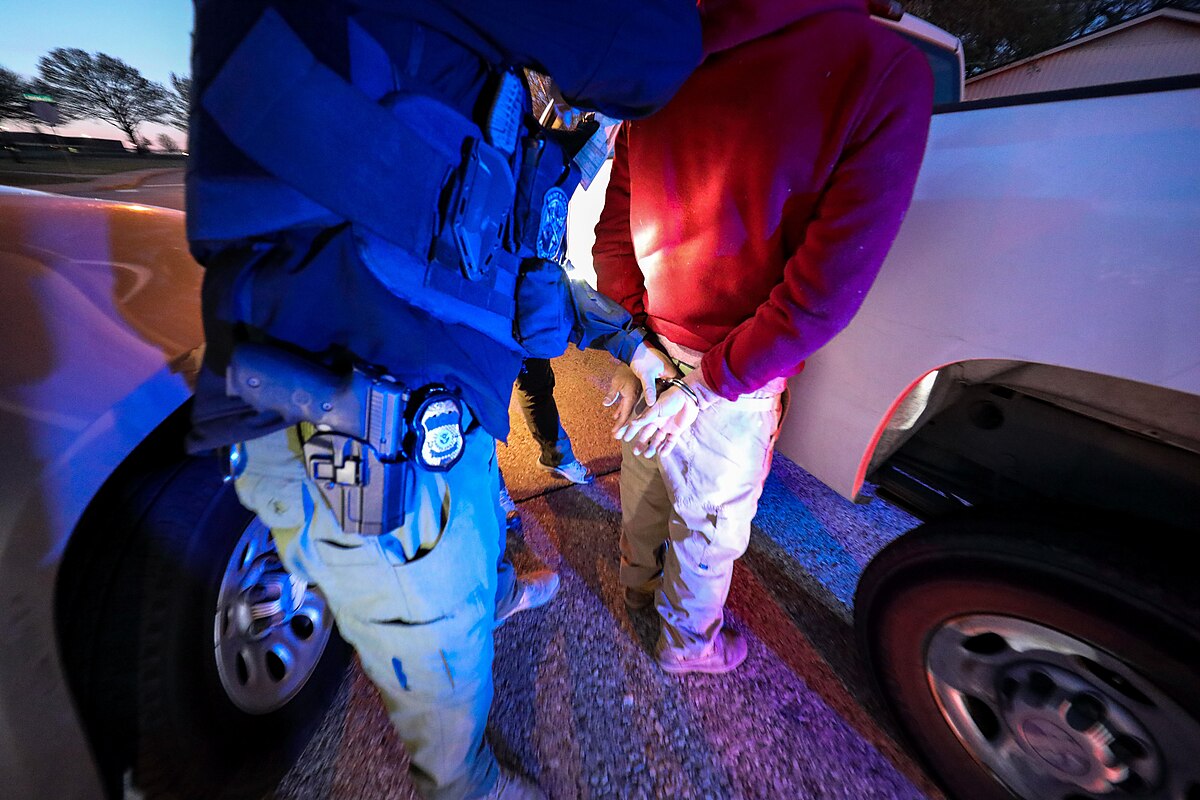

CBP Photography

CBP Photography

The decision handed down by Judge Dolly M. Gee of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California brings into sharp focus the federal government's obligation toward migrant children who enter the United States illegally. The decision is the result of a class-action lawsuit filed by lawyers representing these children, arguing that they have the right to a safe and sanitary environment, even before they are formally prosecuted, according to a report in The New YorkTimes.

The court order, which is effective immediately, puts pressure on U.S. Customs and Border Protection to act quickly to properly house these children. It highlights a heated political and cultural debate about the rights of migrants, especially children, who cross the border without authorization.

The situation is compounded by the overburdening of immigration processing centers in southern San Diego County, leading migrants to wait for hours or even days in makeshift outdoor conditions. The lack of shelter, food, and sanitation in these places raises significant public health concerns, especially for unaccompanied children and young families.

Judge Gee based her decision on the legal custody of the children by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), even though they have not yet been formally detained. She highlighted the government's responsibility to ensure the well-being of these children, including access to adequate medical care.

“During the hot desert days, dehydration and heat stroke have become common problems, according to aid groups, and nighttime temperatures, wind and rain are creating conditions ripe for hypothermia. Doctors are particularly concerned about those elements for children, since many have lower body fat than adults and may be malnourished from their journeys”.

While the order does not set a specific time limit on how long children can stay at the sites, it does require the Department of Homeland Security to process children quickly and transfer them to safe and hygienic facilities.

According to the Times report, lawyers for the children argued that they should receive housing and services under a 1997 consent agreement known as the Flores agreement, which sets standards of treatment for immigrant children in government custody.

In contrast, the government argued that it had no obligation to provide services to the children while they were not formally in U.S. custody, but the court's ruling highlighted that Border Patrol agents' control over the children indicated a form of legal custody.

While the ruling acknowledges the practical difficulties faced by the border agency, it underscores the need to process children efficiently and ensure their well-being during the time they are in federal custody or influence.