- 14 3402-5578

- Rua Hygino Muzy Filho, 737, MARÍLIA - SP

- contato@latinoobservatory.org

Foto: Amuzujoe

Foto: Amuzujoe

The CBP One

app is a tool developed by the United States Customs and Border Protection

(CBP) to facilitate immigration control at the American border. Announced by the White

House in 2020 as part of a series of measures to manage the growing flow of

immigrants, the app would allow asylum seekers to anticipate their applications

and schedule a visit to a port of entry in the United States, avoiding the need

to wait days at the border.

Thus, the

expectation about the app's features was to reduce waiting times and crowds at

US ports of entry, in addition to

reducing the number of people who stay at the border between Mexico and the US,

as well as mitigating the problems associated with these crowds, enabling a

safer screening process, orderly and humane, as communicated

by the White House.

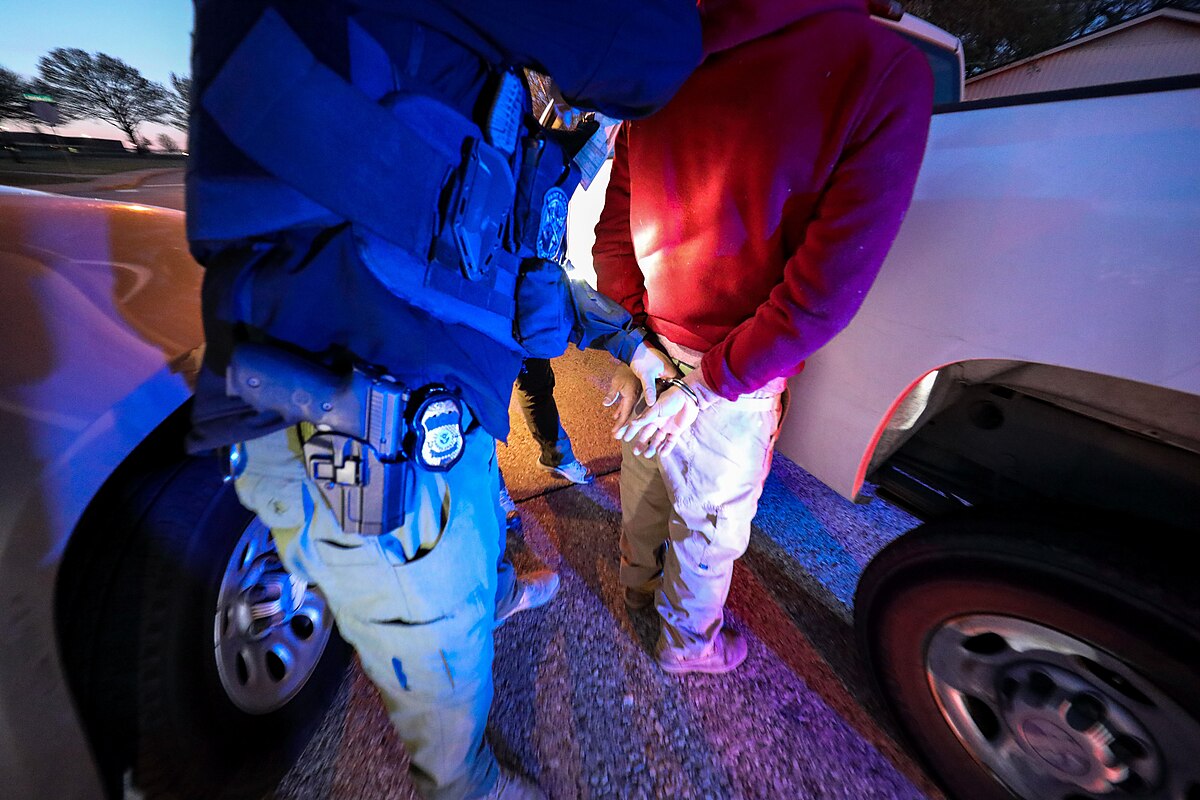

However, this was not what happened from the moment of the announcement. U.S. immigration policy has become stricter: immigrants caught trying to enter the country illegally will now be expelled and subject to a five-year ban, preventing their re-entry during that time.

Because of

this, a marked concern has arisen among entities that defend immigrants and

refugees. This is the case of the Amnesty International report (2024) that

characterizes the practice as a "clear violation of international human

rights and refugee rights", and a malaise that

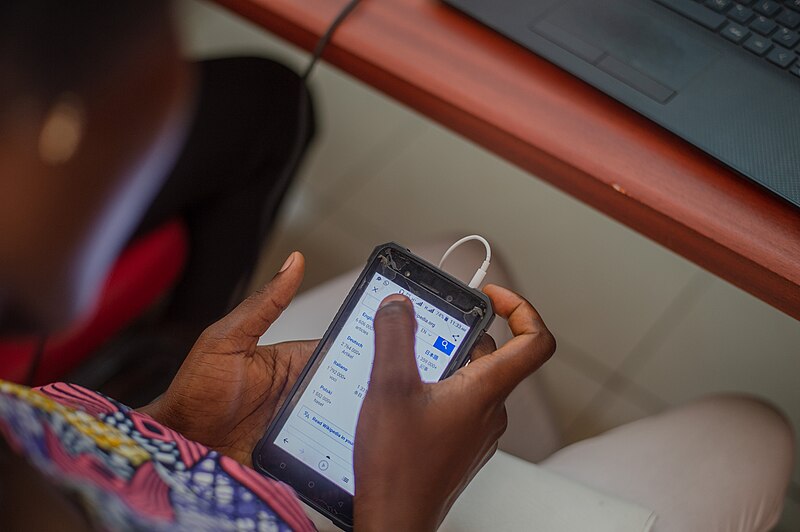

accentuates the issue of technological inequality, since not everyone has a

cell phone or ways to access the internet. Also, as pointed out by Paul

O'Brien, Executive Director of Amnesty International USA, there are fears about

the inappropriate use of personal information provided by immigrants.

Adding to the problem, the use of CBP One has been bolstered by the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways FinalRule, introduced by the Biden administration in 2023, which imposes tough restrictions on those seeking asylum in the U.S. from Mexico via the southern border.

As a result, with waiting times increasing and uncertainty about the allocation of appointments, many asylum seekers are forced to make risky decisions to cross the border into the United States without scheduled appointments, putting their lives at risk and potentially becoming ineligible for asylum due to Biden's "Asylum Ban."

CBP One app makes it difficult for those applying to enter the U.S. to schedule appointments

The lack of stability and accessibility in the use of the application are points that have become notorious in the situation involving CBP One, since, according to the Amnesty International report, many hindrances are involved. These include: the technological barrier, language and literacy limitations, misinformation, and the arbitrary nature of query allocation.

Also, according to the report, the application "routinely crashes" and frequently presents error messages to users, a factor that only hinders the appointment scheduling process for those who need to access US ports of entry. Migrants also face language barriers — such as the availability of the app in only 3 languages (English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole) and the lack of accessibility for those who are not literate — as well as the scarcity of opportunities to obtain an appointment.

Stories that exemplify the aforementioned obstacles include that of Michel, whose last name was not identified. He is a 35-year-old bricklayer from Ciudad Juárez and recounts his frustrated experiences trying to schedule an appointment to ask for asylum: "They are making things difficult" He mentioned that the app suddenly stops, in any of its steps. In addition, to try to schedule an appointment, he needs to work daily on "odd jobs" to make the necessary internet recharges so that his wife can also try to make an appointment.

Another similar case is that of Gloria, a 56-year-old Guatemalan woman who shows confusion about the asylum and asylum processes: "They say you need a sponsor in the U.S., and I don't have one". This statement only reveals the lack of clarity in information for migrants about the asylum requirements for each nationality, since such requirements apply only to citizens of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

Finally, a Mexican woman, who is also seeking asylum, recounts trying to schedule an appointment three months ago and expresses her despair in the face of uncertainty: "I've been trying to make an appointment for three months. I thought the appointments were going in order. It's maddening."

Regarding its presentation, it is interesting to point out that one of the deficiencies involving the use of the application is the fact that it operates in a system of random consultations, providing inconsistent experiences among asylum seekers.

From this perspective, Paul O'Brien stated that "the CBP One app transforms the legal right to asylum into a lottery system based on chance", emphasizing that asylum seekers may never reach safety and security in the United States simply because they may never get an appointment.

Thus, all the unease that permeates the subject is only aggravated by an analysis carried out by Amnesty International's Security Lab that revealed that the CBP One app sends information and device identifiers to Google's Firebase service, something that is not informed to users, bringing to light concerns about privacy, surveillance and possible discrimination.

Digitalization in humanitarianism: an enabler or a new

barrier?

Considering all the problems involving the use of CBP One and starting from the literature of Austin Kocher, Glitches in the Digitization of Asylum: How CBP One Turns Migrants' Smartphones into MobileBorders and Martina Tazzioli, Digital expulsions: Refugees’ carcerality and the technological disruptions of asylum, it is possible to question the entire digitalization in the lives of immigrants in humanitarian processes.

Firstly, Kocher's (2023) work aims to argue that the flaws that permeate the functionalities of the CBO One app, rather than mere accidents, are the result of policy decisions that force vulnerable migrants to rely even more on "experimental technologies" that hinder the asylum application process. Thus, new modern tools limit access to humanitarian aid, as many are unable to overcome digital barriers.

In light of this, many pertinent questions arise (Kocher, 2023): how should we evaluate the government's use of migrants' smartphones as a mechanism to access asylum? Can an agency whose mission is border enforcement be trusted to create reliable software for migrants at risk of persecution while that same agency expands other forms of surveillance that facilitate the exclusion of migrants?

Many points lead to unfavorable answers to each of these questions, since it is precisely with these reflections that Kocher (2023) explains the technological effects on the lives of immigrants through the notion of digital expulsion, introduced by Martina Tazzioli, in which they "govern through disorientation":

1. The vacancies released for scheduling are very limited, being filled quickly. This harms families with many children, as they take longer to enter biographical information, leading some to separate.

2. Initially, the application was launched only in English and Spanish, and is therefore inaccessible to Haitian asylum seekers. Even after the introduction of the Haitian Creole language, the translation quality was evaluated as low.

3. The CBP One app was repeatedly described as "glitchy", that is, it had many unexpected crashes, bugs, and crashes that made it difficult to schedule appointments.

4. The app's facial recognition software, according to allegations, discriminated against migrants with darker skin, so that they could not be properly recognized on the platform.

All these points corroborate Martina Tazzioli's position (2023, p. 1300), in which digital technologies in humanitarianism, for refugees, are mainly used to make it difficult for migrants to become asylum seekers and access rights and financial-humanitarian support.

In addition, through digital expulsions, private and state actors capitalize on the displacement of immigrants through the data-driven economy, in which asylum seekers are transformed into sources of data extraction to justify new interventions and the implementation of new technological systems (Tazzioli, 2023, pp. 1302-1303), something that joins the concern of Paul O'Brien, for fear of misuse of information provided in the app.

The non-neutrality of technology and Amnesty

International's appeal

The dynamics portrayed highlight how digitalization in humanitarianism marginalizes migrants and transforms them into subjects of control, using technologies that amplify surveillance and perpetuate exclusion. When analyzing migration from the perspective of these digital barriers, it is evident that technologies are not neutral; They function as tools to strengthen power structures that limit access to fundamental rights and intensify inequalities. Therefore, rather than serving as bridges to protection and justice, these technological innovations often become obstacles that amplify the precariousness of migrants and further hinder their integration and survival.

It is necessary to mention that the use of technology is not entirely negative, since its beneficent potential is symmetrically proportional to the harm when applied in a planned and inclusive way. However, what is currently observed, in this case, is an incentive to transform asylum seekers into illegal immigrants.

Based on the above, Amnesty International calls on the United States to immediately cease the implementation of the Asylum Ban and the mandatory use of the CBP One app: Ana Piquer, the organization's director of the Americas, points out that while technological innovations can offer safer transit and more orderly border processes, "Programs like CBP One cannot condition and limit the way of seeking international protection in the United States. "Amy Fischer, Director of Refugee and Migrant Rights at Amnesty International USA, for her part, argues that "The United States has a moral and legal obligation to protect all people who seek safety in our country".

As a result,

many cases involving international migrants imperatively require careful and

humane review in order to obtain the substantial reception they need. Since, in

the words of Tazzioli (2023, pp. 1303-1311), the experience of immigrants is

suffocated, confined, and disturbed. They become forced users of technology,

stripped of their time and drained of their lives.